Correspondences, Part 2

Snapshot, stream, snowball: down a rabbit hole of recent reading with Oliver Sacks, Henri Bergson, Zeno of Elea, and other companions.

This is the second part of a three-part essay.

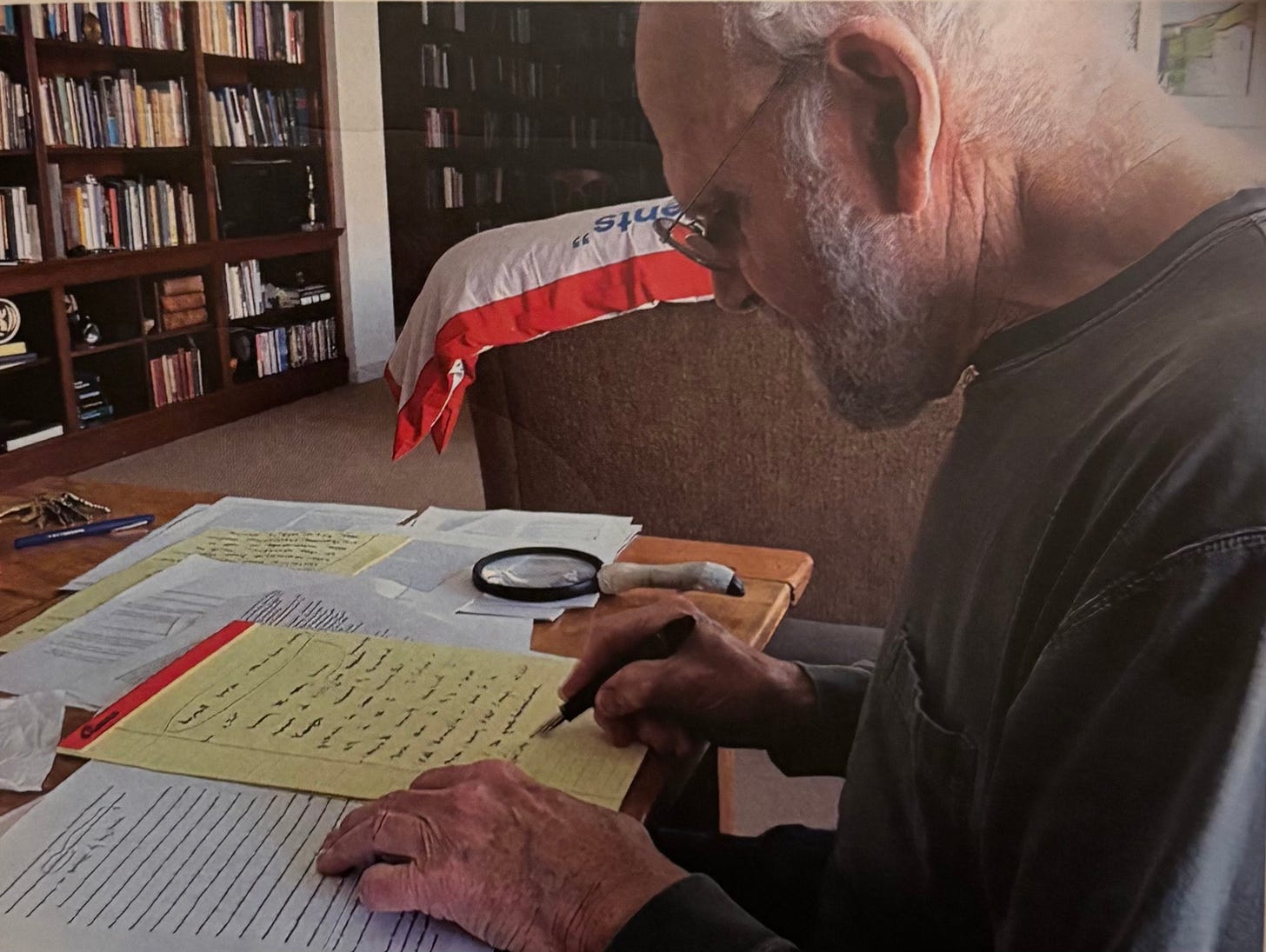

In my last post, I started out to write casually about some recent reading—chiefly Oliver Sacks’s Letters and Emily Herring’s Herald of a Restless World: How Henri Bergson Brought Philosophy to the People—in order to recommend these books to you, but got carried away, leading to the promise of a second installment, which, like the first, has exceeded its intended bounds, prompting me now to promise a third. In short, I went down a rabbit hole and will need a concluding post to climb back out.

This time, I revisit Sacks’s essay “The River of Consciousness” and am conveyed by its current past the fertile landscape of William James’s thinking into the eddies of Bergson’s culminating work, Creative Evolution, where I meet Zeno of Elea and try to keep up with his paradoxes. You’ll see that’s not always easy going, but what follows is a fair representation of where my reading led me. As an homage to Dr. Sacks, whose first editor, Colin Haycraft, once—and only half in jest—accused Sacks of provoking a complaint that required a hospital stay to provide himself with material for another footnote, this installment is replete with its own collection of reading trail markers, gathered at the conclusion.

Let me note that it would be useful to have read part one of this essay before diving in here, as I pick up where it leaves off, with my reading of the two different versions of the consciousness essay.

Both versions of “River of Consciousness” open with a quotation from Jorge Luis Borges, providing a metaphor that Sacks begins to interrogate:

“Time,” says Jorge Luis Borges, “is the substance I am made of. Time is a river that carries me away, but I am the river.” Our movements, our actions, are extended in time, as are our perceptions, our thoughts, the contents of consciousness. We live in time, we organize time, we are time creatures through and through. But is the time we live in, or live by, continuous, like Borges’s river? Or is it more comparable to a succession of discrete moments, like beads on a string?

His inquiry leads to David Hume (“for him,” Sacks writes, quoting from A Treatise of Human Nature, “the mind was ‘nothing but a bundle or collection of different perceptions, which succeed each other with an inconceivable rapidity, and are in a perpetual flux and movement’”), then quickly to William James, who minted the metaphor “stream of consciousness” in his Principles of Psychology. But the ever-oscillating genius of James probes its own coinage, wondering, in his own words, “is consciousness really discontinuous . . . does it only seem continuous to itself by an illusion analogous to that of the zoetrope?”

Zoetropes, Sacks explains, were popular diversions in Victorian households. A sequence of static drawings—“‘freeze frames’ of animals moving, ball games, acrobats in motion, plants growing”—were mounted on a drum; when this was rotated, the separate drawings flicked by so rapidly that they soon were blended into a moving image. “Had James been writing a few years later,” Sacks speculates,

he might have used the analogy of a motion picture. . . . The technical and conceptual devices of cinema—zooming, fading, dissolving, omission, allusion, association, and juxtaposition of all sorts—rather closely mimic the streamings and veerings of consciousness in many ways.

It is an analogy that Henri Bergson used in his 1907 book Creative Evolution, in which he devoted an entire section to “The Cinematographical Mechanism of Thought and the Mechanistic Illusion.”

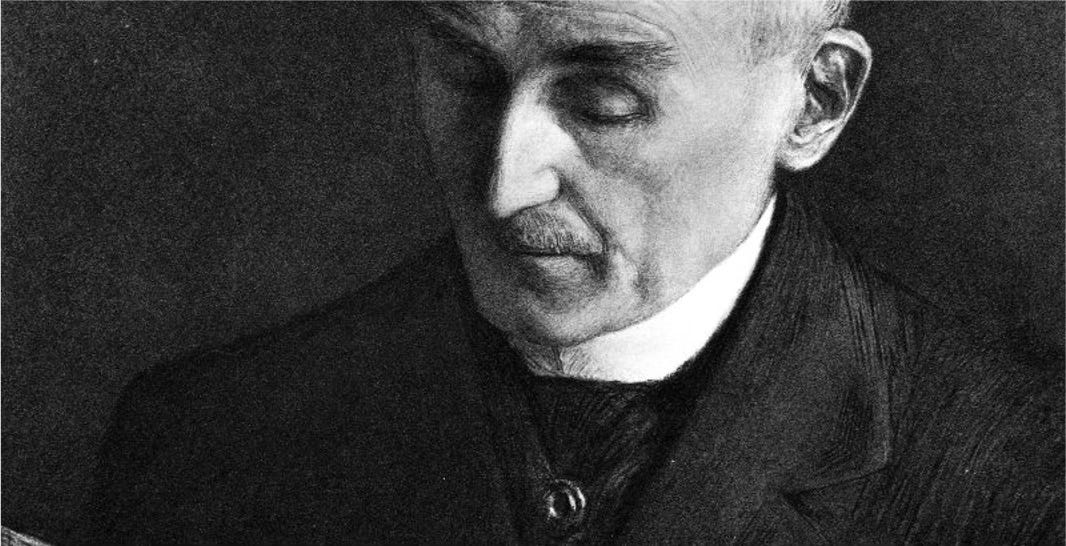

Revisiting “The River of Consciousness” after tracking its gestation in its author’s correspondence1, I met this Bergson reference with fresh interest, for, on the same bookstore visit on which I’d purchased Sacks’s Letters, I’d coincidentally picked up Emily Herring’s Herald of a Restless World: How Henri Bergson Brought Philosophy to the People, the first English-language life of the thinker who had been awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1927. Other than some passing references in Sacks’s writings, what I’d previously known of Bergson I’d largely learned from the short chapter devoted to him in Robert D. Richardson’s superb William James: In the Maelstrom of American Modernism. One sentence from Richardson’s book—“All that concepts can do, Bergson argues, is imprison ‘the whole of reality in a network prepared in advance’”—had stuck in my mind with such presence that I leapt at the opportunity to learn more about Bergson when I heard news of Herring’s biography. Its inviting, fleet narrative does an excellent job surveying its subject’s key ideas and capturing his remarkable early twentieth-century celebrity, both in France and internationally (a lecture he delivered at New York’s Columbia University in 1913 drew such a large crowd it provoked the first traffic jam on Broadway).

In the original version of “River of Consciousness,” Sacks followed up his initial reference to Bergson with a truncated excerpt from Arthur Mitchell’s 1911 translation of Creative Evolution to illustrate the cinematographic analogy he is unpacking;2 for the essay’s book publication, he eschews quotation to unpack it directly:

when Bergson spoke of “cinematography” as an elemental mechanism of brain and mind, it was, for him, a very special sort of cinematography, in that its “snapshots” were not isolable from one another but organically connected. In Time and Free Will, he wrote of such perceptual moments as “permeating one another,” “melting into” one another, like the notes of a tune (as opposed to the “empty and succeeding beats of a metronome”).

Scurrying down the rabbit hole that the tandem reading of Sacks and Herring had opened, I turned to Donald Landes’s 2023 translation of Creative Evolution—much praised by Herring—to find the passage Sacks had originally cited and explore its surrounding context, in which Bergson is imagining the reproduction on a screen of “a lively scene, such as a military parade.” One way to do it, he writes, “would be to take a series of snapshots of the regiment as it passes by and to project these snapshots onto the screen such that they replace each other in quick succession. This is what the cinematograph does.” He goes on (I quote at length to represent the quality of Bergson’s mind and to capture nuances lost in truncation):

With a series of photographs that each represent the regiment in an immobile attitude, the projector reconstitutes the mobility of the regiment that passes by. True, if we were dealing with the photographs by themselves, then as much as we might look at them, we would never see them come to life—we will never make movement out of immobile parts [immobilités], not even out of immobile parts indefinitely juxtaposed with each other. For the images to come to life, there must be movement somewhere. And indeed, movement surely exists here: it is in the projector. Because the filmstrip unwinds, causing the various photographs of the scene to follow one after the other, in turn, each actor in this scene regains his mobility: he strings together all of his successive attitudes on the invisible movement of the cinematographic filmstrip. To summarize, the procedure consisted in first extracting an impersonal, abstract, and simple movement, a movement in general, so to speak, from all of the movements belonging to all of the figures; then, in placing this movement into the projector; finally, in reconstituting the individuality of each particular movement through the composition of this anonymous movement with the individual attitudes [of the actors]. Such is the artifice of the cinematograph. And such is also the artifice of our knowledge. Rather than attaching ourselves to the inner becoming of things, we place ourselves on the outside of them in order to artificially recompose their becoming. We take quasi-instantaneous views or snapshots of the reality that passes by, and, given that they are characteristic of this reality, we can simply string them together—along a becoming that is abstract, uniform, invisible, and situated at the foundation of the apparatus of knowledge—in order to imitate what is characteristic in this becoming itself. In general, this is how perception, intellection, and language proceed. Whether it is a question of thinking, expressing, or even simply perceiving becoming, we hardly do anything other than set into motion a sort of inner cinematograph. We might thus summarize all of this by saying that the mechanism of our ordinary knowledge is cinematographic in nature. [Brackets are Landes’s; emphases belong to Bergson.]

The final sentence drives home that Bergson is talking about how we construct—that we construct—our ordinary knowledge. Whether this is also the mechanism of our visual perception (as Sacks suggests) or even of our neural operations (as Crick and Koch posit)3, Bergson’s argument is an attempt to gain a metaphorical grasp of the way our minds operate when we try to understand the world, isolating discrete elements so we can describe and interpret them. The insight that shapes his cinematographic metaphor is that our working model of the world—a model that may well be physiologically or neurologically determined—conditions us to parse in spatial terms experience that unfolds in another syntax entirely.

One day in the mid-1910s, Herring tells us, an importunate woman buttonholed the philosopher after he’d delivered one of his popular lectures at the Collège de France in Paris. She demanded he express the essence of his thinking in a few words. He replied: “I simply argue, Madam, that time is not space.”

The import of Bergson’s quip is illustrated by his discussion in Creative Evolution of the paradoxes of Zeno of Elea, propounded by the logician in the fifth century BCE to reveal the puzzles posed by motion to our conception of space and time. In one paradox, Zeno asks how, if time is composed of instants, an arrow in flight can be said to move at all, since, at any single moment, the arrow 1) occupies space equal to its own length; 2) is not moving to where it is, since it’s already there; and 3) is not moving to where it is not, because the single instant it occupies fixes it where it is. Therefore, Zeno concludes, the arrow is motionless at any and every instant; further: if time is composed entirely of instants, motion is impossible.

Or consider Achilles and the tortoise. By Zeno’s logic, if the latter is given a head start, Achilles, despite his greater speed, can never catch it, because by the time the runner reaches the reptile’s previous position, the slower creature will have moved on, creating a new gap between them again, and then again, in an incremental game repeated ad infinitum.

Clearly, this is not the way the world works: life assumes what logic obscures. Bergson explains:

Zeno’s trick consists in recomposing Achilles’s movement according to an arbitrarily chosen law.

In a first leap, Achilles would arrive at the point where the tortoise was; in a second leap, he reaches the point to which the tortoise had moved while Achilles was completing the first leap, and so on. This being the case, Achilles would indeed always have a new leap to make. But it goes without saying that Achilles manages to catch the tortoise in a completely different way. The movement that Zeno considers would only be the equivalent of Achilles’s movement if we could treat movement in the same way that we treat the interval traversed, i.e., as decomposable and recomposable at will. And the moment we subscribe to this first absurdity, all of the other ones come along with it.

Bergson intuited that our ordinary knowledge works like Zeno’s logic: it parses reality in discrete steps in order to be able to describe it at any given moment, stripping from life the melody by which notes of time lose their isolation in the music of experience. Bergson calls this melodic reality durée. In Essay on the Immediate Data of Consciousness (1889; generally titled Time and Free Will in English versions), Bergson explained—as he expressed it in a 1908 letter to British philosopher H. Wildon Carr—“that real time radically differs from space in terms of all of its attributes, and that if we place time and space on the same line, if we assume that they have the same attributes, this is because (for the convenience of language and science) we substitute spatialized time for real time, i.e., a space that has become symbolic of true durée.”4

Essay on the Immediate Data of Consciousness was Bergson’s doctoral thesis, and the idea of durée was its central philosophical factor (although this point was lost, per Herring, on his examiners). Richardson, in his biography of William James, gives a succinct description of the notion’s genesis: “Bergson’s life-changing moment of insight came in 1884. While he was taking a walk one day at Clermont-Ferrand, it came to him that the Platonic assumption that the immutable is higher than the mutable or temporal was wrong.” As Bergson would later put it in his Introduction to Metaphysics (1903):

The whole of the philosophy which begins with Plato and culminates in Plotinus is the development of a principle which may be formulated thus: “There is more in the immutable than in the moving, and we pass from the stable to the unstable by mere diminution.” Now it is the contrary which is true.

Richardson again: “Valuing the moving over the immovable, the actual stream over the idea of a stream, led Bergson to his notion of the importance of time as duration, not as stackable chips of a specific size.”

As with time, so with knowledge: our ordinary knowledge, in its processing and propagating of short packets of data (yes, much like the internet), abstracts information from the context that gives it presence and meaning beyond its immediate utility.5 In Bergson’s framework, that context is durée, time as medium rather than measure.

“Durée is the continuous progression of the past, gnawing into the future and swelling up as it advances,” he writes near beginning of Creative Evolution.

As such, our personality constantly sprouts, grows, and matures. Each of its moments is something new added onto what came before. But let us go further: it is not just something new, it is something unforeseeable. My present or actual state is surely explained by what was there in me and by what was acting upon me a moment ago. In analyzing it, I would not find any other elements. But no intellect, not even a superhuman one, would have been able to foresee the simple and indivisible form that gives to these entirely abstract elements their concrete organization. This is because foreseeing consists in projecting into the future what one has perceived in the past, or in imagining, as if in the future, a novel assemblage of already perceived but now differently arranged elements. But that which has never been perceived, and which is at the same time unique, is necessarily unforeseeable. And this is precisely the case with each one of our states, taken as a moment in an unfolding history: each state is unique and could not have already been perceived, since it concentrates in its very indivisibility all that had previously been perceived along with what the present adds to this. Each state is an original moment in a history that is itself no less original.

We may parse our experience as a sequence of moments, but our inner lives collect in an accumulating advent. “The state of my soul, advancing along the course of time,” writes Bergson, “continuously swells with the durée that it gathers—it, so to speak, snowballs upon itself.” Time’s accretive apprehension gives our consciousness a continuity that both connects and transcends the shifting states of instant-by-instant experience, each of which—when we come to describe them—we label as discrete realities.

Bergson:

When we say “The child becomes a man,” let us take care not to fathom too deeply the literal meaning of the expression, or we shall find that, when we posit the subject “child,” the attribute “man” does not yet apply to it, and that, when we express the attribute “man,” it applies no more to the subject “child.” The reality, which is the transition from childhood to manhood, has slipped between our fingers. We have only the imaginary stops “child” and “man,” and we are very near to saying that one of these stops is the other, just as the arrow of Zeno is, according to that philosopher, at all the points of the course. The truth is that if language here were molded on reality, we should not say “The child becomes the man,” but “There is becoming from the child to the man.” In the first proposition, “becomes” is a verb of indeterminate meaning, intended to mask the absurdity into which we fall when we attribute the state “man” to the subject “child.” It behaves in much the same way as the movement, always the same, of the cinematographical film, a movement hidden in the apparatus and whose function it is to superpose the successive pictures on one another in order to imitate the movement of the real object. In the second proposition, “becoming” is a subject. It comes to the front. It is the reality itself; childhood and manhood are then only possible stops, mere views of the mind; we now have to do with the objective movement itself, and no longer with its cinematographical imitation. But the first manner of expression is alone conformable to our habits of language. We must, in order to adopt the second, escape from the cinematographical mechanism of thought.

In “The River of Consciousness,” Sacks follows his pairing of Bergson and James with a passage from the chapter in the latter’s Principles of Psychology called “The Perception of Time,” in which James invites the nineteenth-century thinker James Mill to join the collective pondering on the mechanism of mind. “If the constitution of consciousness were that of a string of bead-like sensations and images, all separate,” James begins, then continues his thought in the words of Mill (which I quote here at greater length than James or Sacks does):

we never could have any knowledge, excepting that of the present instant. The moment each of our sensations ceased, it would be gone, for ever; and we should be as if we had never been.

The same would be the case if we had only ideas in addition to sensations. The sensation would be one state of consciousness, the idea another state of consciousness. But if they were perfectly insulated; the one having no connexion with the other; the idea, after the sensation, would give me no more information, than one sensation after another. We should still have the consciousness of the present instant, and nothing more. We should be wholly incapable of acquiring experience, and accommodating our actions to the laws of nature. Of course we could not continue to exist.

Even if our ideas were associated in trains, but only as they are in Imagination, we should still be without the capacity of acquiring knowledge. One idea, upon this supposition, would follow another. But that would be all. Each of our successive states of consciousness, the moment it ceased, would be gone for ever. Each of those momentary states would be our whole being.

Such, however, is not the nature of man. We have states of consciousness, which are connected with past states.6

For Mill—and, I would submit, even more so for James, Sacks, and Bergson—these states are not tenses of consciousness, set with exactitude in relation to an established and unvarying chronology, but aspects of it, imbued with a transitional fluency that makes their motives shifting, even kaleidoscopic.7 The interruption of their fluency provides the matter for the human dramas Sacks treated with empathy in his practice and portrays vividly in his writing, dramas set in motion by neurological conditions that could seldom be mechanistically explained or understood, for their presenting symptoms—anomalies of perception, communication, embodied awareness, mental alertness and acuity, social presence and affect—reflected a breaking of the very continuity that nourishes self, identity, a life in time.

How do momentary states hold together in our minds to fashion a sentence that finds expression in the world? How are the snapshots of our lives animated with the movement that carries us along the stream of time? On its own, a book of letters might prompt such questions; the fact that they were a focus of Sacks’s professional life makes them all the more relevant to a reading of Letters. But it is when one turns to A Leg to Stand On (1983), a pivotal book Sacks struggled to write for more than a decade between the first publication of Awakenings and the success of The Man Who Mistook His for a Hat,8 that one finds such queries most fully engaged. In its relation of his encounter with a bull on a mountain in Norway, the surgery required to repair the severe leg injury that resulted, and the profound alienation from his limb that followed as he struggled to learn to walk again (culminating, as Sacks writes, in “the most eventful and crucial ten minutes of my life”), A Leg to Stand On not only poses but enacts such questions, as I will discuss next time.

Here’s the passage from the Mitchell translation of Creative Evolution as Sacks quotes it, having made several elisions; the emphasis at the end is in Bergson’s original.

We take snapshots, as it were, of the passing reality, and…we have only to string these on a becoming, …situated at the back of the apparatus of knowledge, in order to imitate what there is that is characteristic in this becoming itself…. We hardly do anything else than set going a kind of cinematograph inside us…. The mechanism of our ordinary knowledge is of a cinematographical kind.

Again, see part one.

It is one of the happier coincidences of intellectual history that the woman who would become Bergson’s wife, Louise Neuberger, was a cousin of Marcel Proust, who served as best man at their wedding and who, though he denied direct influence, gave magnificent fictive expression to the philosopher’s intuitions about the protean manifestations of real time.

One might reflect further on the internet analogy: knowledge constructed of short packets of information can be applied profitably to many problems; but without embodiment in time, without anchoring in context or immersion in durée, it may drift as far from reality as the certainties of Zeno’s logic (or, more troubling still, redefine both knowledge and reality to fit its sense of profit).

This passage is from the “Memory” chapter of Mill’s Analysis of the Phenomena of the Human Mind (1829). The author was the father of John Stuart Mill.

The words “set with exactitude in relation to an established and unvarying chronology” are borrowed from a 1940s commentary on Russian language by Edmund Wilson, collected in the posthumous volume A Window on Russia. Let me share a portion from it here, since I’ve always delighted in its exhibition of the author’s distinctive fondling of new learning as he meets it, and in how it champions the ingenuity of grammar, which can carry and characterize experience in ways mere data cannot: “It is one of the peculiarities of the Slavic verbs that, besides having several of the usual kind of tenses, they are subject to metamorphoses called aspects.”

When one has become really familiar with the Russian conception of aspects and has ceased to attempt to force them into the Western conception of tenses, one comes to understand for the first time the Russian perception of time—a sense of things beginning, of things going on, of things to be completed in the future but not at the present moment, of things that have happened in the past all relegated to the same plane of pastness, with no distinction between perfect and pluperfect; a sense, in short, entirely different from our Western sense of clock-time, which sets specific events with exactitude in relation to an established and unvarying chronology. The timing of much Russian literature—of Pushkin and Tolstoy—is perfect; but it is not like the timing of a well-made French play, where the proportions, the relations and the development have something in common with mathematics. It is a timing that plays on our most intimate experience of the way in which things happen, which appeals to the natural rhythms of an alert and unregimented attention.

In his most comprehensive autobiographical narrative, On the Move (2015), Sacks writes of its composition: “the writing—the incessant writing and tearing up of drafts—continued. I found Leg more painful and difficult than anything I had ever written, and some of my friends . . ., seeing me so obsessed and so stuck, urged me to give the book up as a bad job.”

Wow! This is exactly where my questions begin to sound so flaky..

Keep going—Please,

We need you on the job!