Correspondences

On the letters of Oliver Sacks and other recent reading.

This is the first part of a three-part essay.

I am generally reading more than one book at a time, so I suppose it should be no surprise that sometimes they strike up a conversation with each other. What follows, originally intended to be a casual chronicle of what I’ve recently enjoyed encountering between covers, has turned into a colloquy tracing rhyming ideas and images across the pages of a few volumes released this past November: Letters by Oliver Sacks; Herald of a Restless World: How Henri Bergson Brought Philosophy to the People by Emily Herring; and Over to You: Letters Between a Father and Son, by John and Yves Berger. Since the books are newly published (rather a rarity in my bookish life these days), their convocation has been shaped in large degree by serendipity. Reading, no less than life, is a chain of chance; still, with books as with experience, our affinities make their own luck.

Over the past year I’ve spent a good deal of time reading and reflecting on the work of Oliver Sacks, resulting in The Soul’s Inning, a piece I posted a few months back. As a believer in book-destiny, I took the November publication of the neurologist’s Letters as a reward for my labor. The large volume runs to some 700 pages, but it’s just the tip of the author’s epistolary iceberg. “His sheer output of letters was prodigious,” writes Kate Edgar, Sack’s long-time editor, who assembled the collection with diligence and deftness. “The correspondence files in his archive include something like two hundred thousand pages—some seventy bankers boxes full.”1

Letters begins in 1960, about a month after the author’s twenty-seventh birthday. Having emigrated from his native England to America, he embarks on an extended odyssey of personal and professional discovery. Over the next decade, on an often uncertain course toward the enduring mission that would realize itself in his 1973 book Awakenings and the career of neurological inquiry that gathered confidence in its wake, this wandering will encompass prodigious feats of weightlifting, motorcycling, and drug-taking alongside intimate liaisons, scientific investigation, and patient care, with profound currents of friendship and despair running beneath the surface activity. The letters covering this period to family, friends, lovers, medical associates, and assorted acquaintances and correspondents—as throughout the collection, many are quite long—amount to something of a picaresque, if one can imagine a picaresque composed jointly by Walt Whitman, Thomas DeQuincy, and a clinical savant with a penchant for unhurried observation.

One sees all the facets of Sacks’s brilliance playing hide and seek in the thicket of his ramifying prose, which would develop in his later books into an instrument of elegantly fusty and eloquently immediate sensitivity, concentrating in its insight not only centuries of medical and natural historical lore but two hundred years of English style as well. His metaphoric gifts, lightly dispensed, light up nearly every page; it’s unlikely that you’ll ever come across a more arresting image of metropolitan night than this, from a self-lacerating and passionate appeal to a distant lover written in 1965:

The New Jerusalem, its billion windows golden in the setting sun. The creation of the New York night, a monstrous ganglion come to life. Whose lamp is this, and whose is that? Cameos of 10 million lives.

It’s a passage that evokes, with new electricity, the alertness of the London scenes in Wordsworth’s Prelude. What makes Sacks’s writing—in his letters as in his case studies, essays, and narratives—so singularly expressive is its recourse to poetic apprehensiveness not to transcend but to understand what he absorbs through his looking and listening; the continuous dialogue of metaphor and observation makes his renderings both lively and true to life.

While the narrative arc of Letters becomes less adventuresome as Sacks assumes professional stature and settles into the literary celebrity that The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat would bring him, his long pursuit of existential description—an active figuring out of the sensations and fluctuating resonances that make up our minds—remains paramount. In an April 1985 letter to Evelyn Fox Keller about A Feeling for the Organism, her biography of the geneticist and Nobel laureate Barbara McClintock, Sacks articulates conversationally the credo he’d given almost visionary voice to in A Leg to Stand On, issued the previous year:

. . . what frightens me is not the acquisition of new viewpoints, but the loss of that ancient and fundamental “feeling for the organism.” This feeling imbues the best XIXth century Medicine, all “naturalistic” Medicine, but has become, or can become, a total casualty with “Science” or, at least a certain, narrow sort of scientific method and approach which, as McClintock says (p. 201) cannot give us “real understanding.” What I found marvellous in the last chapter of your book, is her holding to this fundamental, naturalistic “feeling” or “vision,” but renewing it, deepening it, with a unique and new insight so that Nature and Science are totally fused. It is this which seems to make her so extraordinary a figure—at once “old-fashioned,” Victorian, and at the same time a “prophet,” at least precursor, of a scarcely-imaginable future: at once XIXth and XXIth century. This is the kind of neuro-science which I dream of . . .

And it’s the kind of neuroscience he would bring to an enormous audience in the soon-to-be-published Man Who Mistook and all the works that would follow.

Although close reading of Sacks’s oeuvre is by no means required to enjoy Letters, with its extraordinary roster of correspondents, including an array of authors, editors, scientists, thinkers, and public figures that ranges from W.H. Auden to Robin Williams, familiarity with it does provide an extra layer of pleasure as one traces the unfolding of curiosities and dispositions that would ultimately find poised and polished presentation on the pages of his books. A case in point is the discussion of visual consciousness that forms a thread through several letters from late Spring 2003 to neuroscientist Christof Koch and his research partner Francis Crick (of double-helix fame). These newsy missives, accompanied by exchanges of finished texts and manuscripts in progress, allowed me to observe a convergence of interests that would inform an essay of Sacks’s that I especially valued.

On May 8, Sacks writes to Koch about a paper by him and Crick, “A Framework for Consciousness,” that had appeared a couple of months earlier in the journal Nature Neuroscience:

I thank you for the summary paper you wrote with Francis—and, as it happens, I have read it, and several times, with great attention and admiration. One reason for doing this is that I have especially been thinking of motion perception, and its disorders, and its possible mechanisms, myself, as well as some of the broader problems of consciousness. (I think I got scared off the whole subject back in ’92, and took refuge in chemistry and botany for a decade; but now I am back.) I take the liberty of enclosing this* too, and will send a copy . . . to Francis as well, especially as it draws on and quotes your paper with him. It is only a manuscript, rough and provisional, though I hope it may become an article for the NY Review of Books. [*Untitled essay manuscript of what would eventually become “In the River of Consciousness.”]

Crick and Koch had proposed the hypothesis that—as Kate Edgar deftly summarizes it in a footnote—a visual scene consists of discrete “frames” or “snapshots” which are endowed with continuity by the brain rather than by external reality. Writing to Crick two days after his letter to Koch, Sacks tells him:

I was very fascinated by this, especially your “snapshot” proposal, because I have long been interested in motion-perception and its disorders, and have often wondered whether one uses “frames” or “snapshots” in real-life, as well as in the cinema. I had already started writing about this when I received a copy of your paper with Christof—and now (though I don’t usually send out manuscripts which are still being revised) I take the liberty of sending you my “consciousness” piece, because it draws heavily on your own thoughts towards the end.

In mid-June, Sacks reports to Koch:

I have not yet heard whether the NY Rev. Books will publish the piece, and, if so, in what form—tho’ the Editor has told me that he “likes it,” though also that it may be “too long,” unless abridged. So I await further word. I have some impulse, I confess, to add to the piece, to deal with “the stream of consciousness” since the piece started off, initially, as a sort of meditation on “time” . . .

The piece in progress that Sacks is describing would appear seven months later in the New York Review of Books as “In the River of Consciousness” (sans the initial preposition, and further revised, it would become, thirteen years on, the title piece in a posthumous collection of essays, The River of Consciousness). I had read “The River of Consciousness” with a great deal of attention more than a year before I came upon these letters; it had informed the thinking I was doing in preparation for writing “The Soul’s Inning.” So I was eager to revisit it when I came upon the letters to Crick and Koch that Sacks had sent while the essay was being composed. Not only did I delight in re-reading a piece that I admired with a new understanding of its backstory, I had fresh satisfactions in store, courtesy of the good fortune that led me to a biography of Henri Bergson and the letters of Berger père et fils at the same time as I was swimming in Sacks’s river—all of which I hope to detail in my next newsletter.

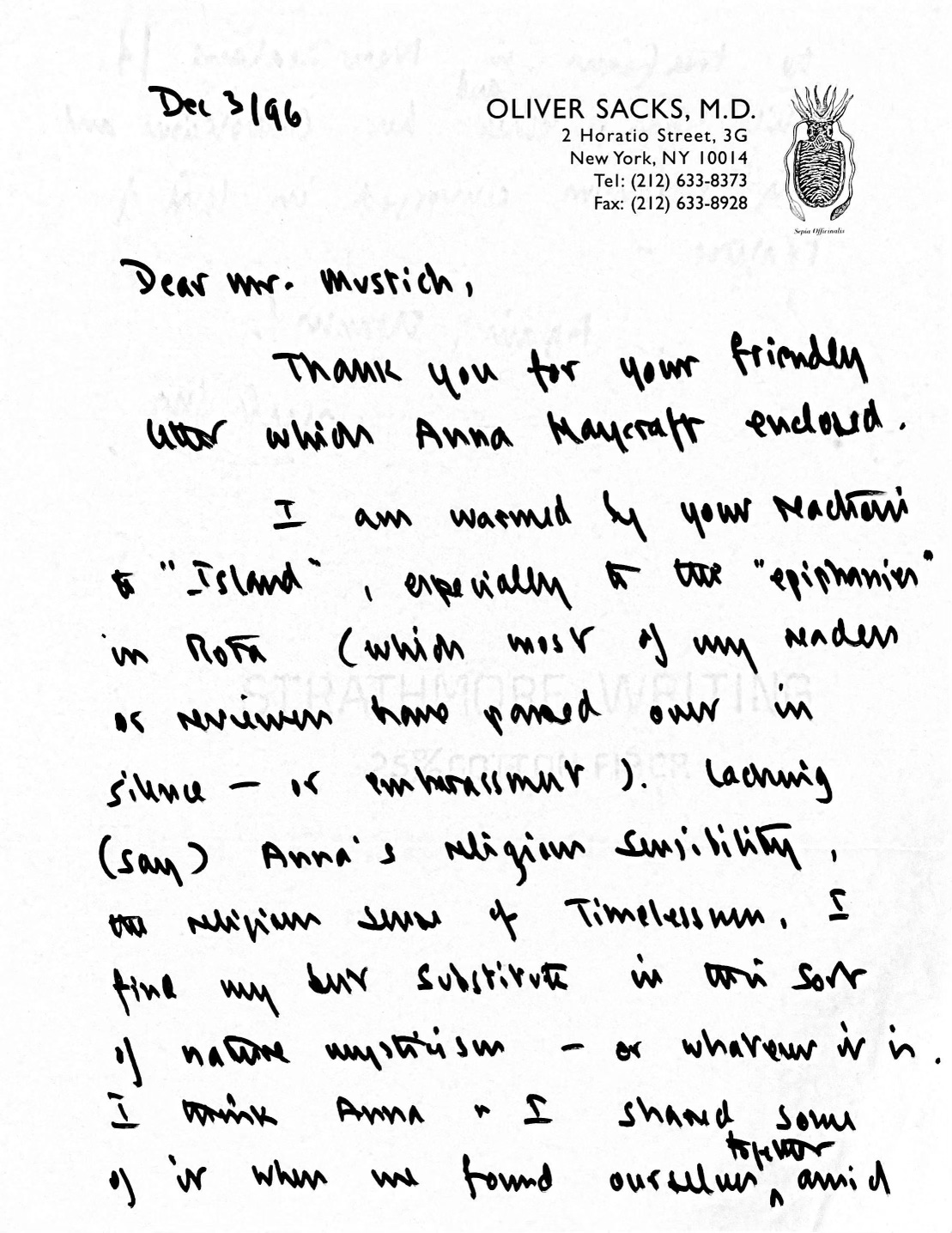

In one of those boxes may be the exchange I had with Sacks in 1996. I’d written him a note—delivered through the good office of his friend Anna Haycraft, whose pen name was Alice Thomas Ellis and whose novels I admired enough to have a hand in reprinting in the United States (I’ve written about Ellis’s novels here). I’d just read the galley of Sacks’s latest book, The Island of the Colorblind, and been moved by it: “The shifting perspectives the new book explores, between the islands of time that define individual neurological realities and the vast continents of time—the ‘deep time’—the natural world inhabits, evoke the apprehensive mysteries of existence with uncanny grace and power. Your discovery, in the cycad forest on Rota, of what I can’t help but think of as ‘a species of eternity,’ in which the enthraller Time assumes the dimension of a liberator, strikes me as a profound, pregnant conclusion to the work you've done to date.” He responded: “I am warmed by your reaction to ‘Island,’ especially to the ‘epiphanies’ in Rota (which most of my readers or reviewers have passed over in silence—or embarrassment). Lacking (say) Anna’s religious sensibility, the religious sense of timelessness, I find my best substitute in this sort of nature mysticism—or whatever it is. I think Anna & I shared some of it when we found ourselves together amid the tree ferns in New Zealand a while back, and her Catholicism and my paganism converged in love of nature.”

If his first sentence alone doesn't hook you I am not sure what to say! Brilliant and now down the rabbit hole I happily will go!

I adore your book “1000 books to read…” You have introduced me to the most amazing reads I wouldn’t have discovered without your book. It’s a prominent book on my shelf as I love reading about as much as books as much as reading them. Ha! Thank you!