Block Island (2024)

I am standing on the shore, my feet in the softly breaking wavelets that roll toward land. I am looking east from Block Island at the expanse of the Atlantic Ocean, a blue-green meadow of breathing water that occupies my field of vision to north and south, at least until it meets the horizon in the distance, where the sky is similarly expansive in its lighter blue aspect, content in its start-of-summer warmth and stillness. Only the wispiest of clouds cross its mantle of serenity, like passing gestures of the day’s allure.

I am thinking of my mother on what would have been her ninety-fifth birthday had she not passed away three years ago. She loved the beach: sitting on the beach, walking on the beach, swimming at the beach, getting ready to go to the beach—the very idea of the beach was a beacon for her spirit. Its light could be bright with sun like today’s, or sheathed in the grayness of weather going out or coming in, the clouds reflecting it distinct in shape or formless as the future, settling in like a bad mood or scudding over the water like flights of fancy, stationary with certainty or aloft in unknowing. It was the vista she loved, the sense of promise sea and sky could summon without reference to the truths and consequences of her inhabited world and its habiting demands, except of course to the children or grandchildren busy in the sand nearby, intently doing and absorbed in their labors, digging in the sands of time that seem infinite in this seaside setting—until an urgent alarm breaks the spell: “I’m hungry.” “I’m cold.” “I’m hot.”

“I’m here.”

Bermuda (1950)

I have a flickering memory of a home movie of my parents on their honeymoon. The film flickered even at my first teenaged sight of it, for the images—of figures giddy in their unaccustomed posing, caught by a camera tipsy with the elixir of fresh technology—didn’t occupy the screen as much as vibrate within it, haunting the flat space of our viewing with weightless, soundless effervescence.

That effervescence, like the lithe bodies that enacted it, seemed to emanate from another dimension than the one I knew my parents to inhabit, the one in which my sister and I assumed our own centrality. Call it youth, for that’s what it is was: they were just over twenty years old, embarking on their life together with a carefree confidence. The same élan, I can only imagine, had accompanied them out of their respective home bases as they took their high school romance into adulthood and Manhattan, she to work in an office at Metropolitan Life off Madison Square Park, he to manage co-op grocery stores, on 8th Street first, then 125th. They’d meet after hours to grab a bite to eat or see a show, I was startled to learn when they reminisced under my questioning decades later—why was it so hard to picture them traveling to and from the Bronx by elevated and underground trains, part of the teeming motion of New York City? Perhaps because I had never seen them ride such transport, their lives having moved on soon after I arrived to the wilds of the northern suburbs, only twenty-one miles by car from their upbringings but, in the minds of their families, across the border of the known world.

What led them north were groceries: another store, his own. Even though the store soon burned down, to the devastating loss of all but life, they’d stay put in the happily named Pleasantville for the rest of their long lives. A butcher shop and then a bar and grill arose from the ashes of the grocery, with new careers ensuing for each of them after that as they managed to reinvent themselves as the tides of time demanded, moving from one apartment to another, and finally—not too long before I saw that honeymoon movie—to a house they’d occupy for nearly sixty years, and in which they both would die.

That 8mm film, as I recall, had but one shot of the newlyweds together—in the backseat of the car that would take them from Williamsbridge to Queens and the airport on their way to Bermuda, the camerawork courtesy no doubt of a bridesmaid or groomsman—before the pictures gave way to single figures: mostly the bride exuding her delight on the sand at Elbow Beach, with one or two glimpses of our future father gamely pretending not to be a fish out of water, as far from his neighborhood as he would ever be. The destination, I’m sure, was my mother’s idea, a response to an allure that pulled her beyond the pale of post-nuptial holidays more usual for their Italian-American set; it was 1950, after all.

Or before all, as far as I was concerned: I would be born five years later, twenty-two months after my sister. We weren’t there, on the beach on an island in the Atlantic, at the start of their lives’ long summer; it was bracing to see them so many things—coltish but graceful, hale and happy—without us.

Tides (1949, 2016)

I am looking at a photograph unearthed as I sorted through the unbound scrapbook—disordered by time and squirreled into hiding places through the creeping disarray of decades—that was the family archive. This was after her death in February 2021, and my father’s passing eighteen months later, when their home of more than sixty years had, with mortality’s definitive punctuation, completed at last its slow migration from the present tense into the vacant and redolent release of the retreating past.

The sepia-toned studio portrait must have been taken in the run-up to her wedding. She’s standing, leaning gracefully on the back of a chair. Right foot half-stepped with care in front of her left, her ankles anchored in heels, she poses with more self-possession than self-consciousness. Bare calves extend beneath the hem of her long linen skirt, its pleats a cascade of cloth that commands remark with a presence—an almost-but-not-quite-rumpled poise—that our easy-care fabrics no longer muster. A darker hued three-quarter-sleeve blouse matches the formal mood of the drapery that falls behind her, its folds a landscape filling the frame to right and left of her figure, but parted in the center to expose a column of shadowed light against which her torso and her head are set off. Her face is shown straight-on, her gaze pensive as it focuses downward to her right, underneath the camera eye. Her right elbow rests on her left wrist, and the forefinger of her right hand is extended upward to support her chin, like an absent-minded homage by the photographer to a forgotten Leonardo. She is beautiful and expectant, an aspiring actress auditioning for the life she’d like to lead.

How stylish she was—and wanted to be. This shouldn’t strike me with the surprise it does when I discover the picture, but to see the motive fully formed so early reminds me how true it would remain throughout her life. Once in her last years, when she seldom left the house, I took her to the eye doctor and then to be fitted for new glasses. Displaying his wares, a young optician opened trays of frames—it was an upscale shop, with wooden cases caching the bulk of the stock—and began suggesting a few for her to try on, but nothing struck her fancy. He opened and closed a tray quickly, thinking its contents, I’m sure, too modish for his quiet client; as he opened the next one, I stopped him, having seen a pair I knew she’d like.

“Go back,” I said. “The tray you just shut.” He opened it.

“Any of these?” I asked her. She pointed to the pair I would have bet on, tortoise shell and round and thick, distinctive: a statement of intent and intuition.

“Are they expensive?” she asked me as sat at the table to have her measurements taken. They were.

“Not enough,” I said.

What is style but a desire for expression? Like most desires, it begins with flirtations and impulsive fumblings, then, if it’s lucky, finds a footing to both anchor it and propel it forward. In that studio portrait of my mother—taken when she was nineteen or twenty, on the cusp of marriage and a new life—there is little sign of diffidence, no hesitation apparent in the assurance she presents. How much of the pose is hers, how much the stock-in-trade of the photography studio is impossible to say, but the image assumes a sense of self—a forthrightness—that she would dress and carry through most of her life.

Like most desires, too, a sense of style can flatten or fatten with age, but she held on to hers through all the distortions of mind and body that midlife demands of even the happiest parent, as children overtake one’s sense of self with the sense of others always with you, obscuring what had once been far-seeing aspirations with everything you have to do right now. As kids come and then go in the momentous fleetingness of childrearing—so endless in its countless hours, so fugitive in its years—how easy it is to lose one’s fettle, to get stuck in a place as pleasant as it is not exactly what you’d had in mind; how hard to break that loving spell and regain one’s tone and poise, as she would do with an ardor I didn’t recognize at the time, but admire now in retrospect with as much amazement as struck me watching that film of her honeymoon when I was fourteen.

As I admire, in the exact sense, a photo of our young family before a fireplace in the apartment we lived in before the one I remember growing up in, mother and father seated—she in an elegant black dress, he in suit and tie—with daughter and son (are we five and three?) at attention in fine attire also, all beaming on cue, and genuinely. “How did she ever get Dad to pose for this?” I asked my sister when we pondered it after their passing. “It’s hard to believe,” she said. But there they are, for the record, smiling at what they looked forward to—and, mostly, got.

Sherwood Island (1961, 2024)

I must have passed the sign a dozen times before the day I noticed it: Exit 18, Sherwood Island Connector. It was a little beyond the normal orbit of our driving since we’d moved to Stamford three years earlier, but not by much—one more exit, another mile or two. Nonetheless, that morning I was delighted to see it and find it so close to home, maybe twenty minutes without traffic.

My delight sprang from memory. My mother had taken us to Sherwood Island on long ago summer days. Back then the state park on the Connecticut coast seemed a distant destination, although it couldn’t have been much more than an hour and change from the village we lived in across the border in New York, even in those days of slower cars. Still, the name had always evoked remoteness for me, perhaps because it possessed when I was small the allure an outing always has for kids, an adventure beyond familiar bounds. (I suppose it didn’t hurt in the evocation department that it chimed in my childhood head with the verdant haunts of Robin Hood.)

What I remember from those trips is the sylvan setting of the beach, the trees supplying recollection with a canopy of boughs to shade blankets spread on the lawn, a screen of time to frame in the mind’s eye what seems a view from the high branches of another, taller tree, and beyond that leafy lens the waters of Long Island Sound. Between these two scenic orientation points—one shadowed and green, one blue and sun-glinted—was the real locus of the visit: a beach awash in pebbles and shells. The strand required light-footed concentration to traverse if one were to splash or swim in the gentle waves; no beach shoes in those days, although old sneakers served just as well if one had a pail to fill and an eye for the unearthly curves of carapaces or a feel for the sensuous fascination of stones rubbed smooth by time.

For decades I’d secreted the setting inside an inner landscape as a kind of refuge, a memorial to boyhood, an allusion to what I loved about being loved by my mother in a way that, across both my formative and my stultified years, enlarged the imagined range for self to move in.1 Now that same self, on the shore of its own old age, moved past the unexpected highway sign with a resolution to take the exit it advertised one day soon, following the Connector to whatever kinship the heart might exhume.

My first attempt to get there was derailed by a momentous traffic jam. After forty minutes idling on the interstate, I took an earlier exit ramp, as if I’d received notice that there was too much busy world between action and contemplation to make transit to the past so simple. A few weeks later, trying again, I arrived in no time. I was amused to discover that the impressively named “Connector” was about a half mile of normal roadway that led from the highway to the park, bridging the network of creeks and streams that earned Sherwood—just barely—the designation “Island.” I parked and walked toward the pavilion, its snack bar and picnic tables lonely in the pre-season quiet. I surveyed the prospect beyond it, then sauntered off into remembrance, beckoned by the trees that invited it.

What had been in memory a cozily shrouded outlook, a proscenium of sorts for the shoreline, was on this morning of reacquaintance—a startlingly sunny day—an expansive terrain of lawn with attending trees that set the stage for two separate beaches. It was a vista to see across rather than into, a panorama more open and unguarded than the private copse my heart had so happily been hoarding, but nonetheless restorative for that. The wide sky waylaid my looking, its blue pellucid and unfathomable, a significance demanding attention but suspended in beauty. When I was little, I couldn’t look that far.

I’m here again, but she is not. My vision skitters across the shimmer of the Sound to the horizon: “Longing, we say,” writes the poet Robert Hass, “because desire is full of endless distances.”

The Shores of Light (1959)

I have no memory of my mother reading to me as a child. Books were such a large part of her life, and would become so central to mine, that I am puzzled by this lack. Surely she read to me often: how else did I come to have such visceral recall of Robert Louis Stevenson’s A Child’s Garden of Verses, or the prayers of Christopher Robin? Those are the kinds of reading she would have treasured, with their overtones of an idyllic storyland far from our own lives—not because she needed to escape, but because such imaginary destinations nourished emotions she knew, tending a heart too tender (as more hearts are than common sense can credit) for the nickel-and-diming of the world-at-large to sustain. Loveliness, like eloquence, shapes its own reward, which abides as a furtive presence within the economies of disappointment no fortitude can afford to forego.2

If I don’t remember her reading voice from my earliest days, her love of reading hovers over me still like a benediction, replete with dispensations and relics. One of the latter sits on the table to my right as I type, salvaged from seas of time by the affection it has always buoyed in me: The Illustrated Treasury of Children’s Literature, published by Grosset and Dunlop in 1955, edited and with an introduction by Margaret E. Martignoni, formerly—I note on the title page—Superintendent of Work with Children at the Brooklyn Public Library.

Mom must have read to us a lot from this—it has the weathered character of a ruin: spine missing and binding broken, the boards of its covers worn from use and completely detached from the book block they were once secured to but now encase only with the aid of a rubber band. That this treasured volume was very much my sister’s is attested by the inscription of her name in three places: at the top right of the opening endpapers, in red ink and what looks like her adolescent hand; on the half-title, where, also upper right, a fledgling writer’s penciled scrawl asserts: This Book is Cathy Mustich’s; and, beneath the title on the same page, where she has applied, in colored pencil and wobbly, elementary cursive, her signature. Was she determined to keep it out of her book-loving little brother’s possessive hands? No doubt. But by the time we’d entered our fifties and most points of contention had lost their point, she was happy to let me take custody. So here the large tome sits, 7 ¾ inches x 10 ¼, more than 500 pages of two-column text with two-color illustrations throughout and the occasional burst of full-color imagery.

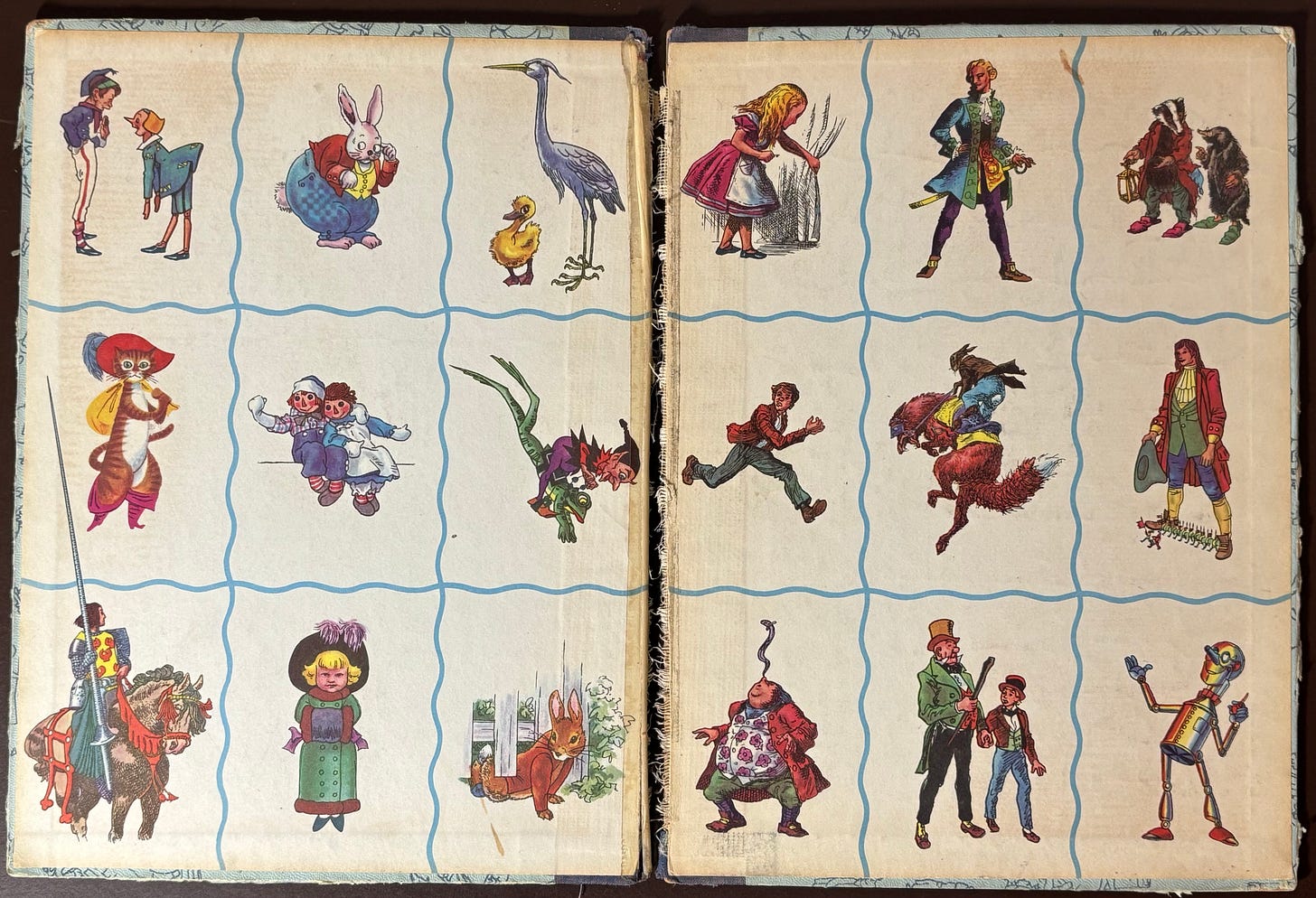

The vivid endpapers display a gallery of characters in styles that mimic their original illustration: there’s Pinocchio and Puss in Boots, Peter Cottontail, Raggedy Anne and Andy, Alice in Wonderland, the Tin Man of Oz, an Arthurian knight, Mole and Badger from The Wind in the Willows, Gulliver attended by Lilliputians. This array gives fair indication of the multifarious contents that follow, a remarkably broad menu of nursery rhymes, poems, fairy tales, stories, and smartly chosen excerpts from classic narratives and novels that proceeds from the simple to the sophisticated (with apt diminishment of type size) across an inviting mix of genres and styles. First come the sound-based scamperings that give the playfulness of words its due: “Hickory, Dickory, Dock!” and “Three Blind Mice” and many others of that ilk, still resounding in perfect recall across my three score and ten as they are awakened from their slumbers. “Little Miss Muffet” and “Hey, Diddle, Diddle!” and “Twinkle, Twinkle”—how many times must my mother have spoken these to me for them to have abided so long beneath the oceans of words that have washed over them since I was small? It’s listening that first teaches the tact of writing, enacting in the sway of rhythm and the ricochet of rhyme the texture of sound as it feels its way toward sense, giving form to expression even as it extends—and sometimes explodes—it.

Jack be nimble,

Jack be quick,

Jack jump over

the candlestick.Echoes, resonances, melodies march across the early pages of the collection like foot soldiers marshaling the music of childhood, consorting with nonsense or assembling in tiny anthems:

Ride a cock-horse To Banbury Cross, To see a fine lady Upon a white horse, With rings on her fingers And bells on her toes, And she shall have music Wherever she goes.

The panoply of rhapsodical poetry segues into stories in prose—“Two Happy Little Bears,” “The Tale of Peter Rabbit,” and “The Poppy Seed Cakes” for a start—before another selection of verse, from the likes of A. A. Milne and Kate Greenaway and—how could I have forgotten him and his orchestrated staircases of rhyme?—Eugene Field:

Wynken, Blynken, and Nod one night

Sailed off in a wooden shoe,—

Sailed on a river of crystal light

Into a sea of dew.

“Where are you going, and what do you wish?”

The old moon asked the three.

“We have come to fish for the herring fish

That live in this beautiful sea;

Nets of silver and gold have we,”

Said Wynken,

Blynken,

And Nod.That’s the first stanza of the poem that inspired the costumes my sister and I—and our friend from down the block, Johnny Vinchot—wore on what must have been one of my earliest ambulatory Halloweens. In the creased black-and-white snapshot that documents the occasion, our faces shine with the innocent mischief that is the passing glory of happy childhoods.

Wynken and Blynken are two little eyes,

And Nod is a little head,

And the wooden shoe that sailed the skies

Is a wee one’s trundle-bed;

So shut your eyes while Mother sings

Of wonderful sights that be,

And you shall see the beautiful things

As you rock in the misty sea

Where the old shoe rocked the fishermen three:—

Wynken,

Blynken,

And Nod.Coming upon this poem—it’s set across two pages and surrounded by an embrace of dreamy visual evocations of its characters’ voyaging—I exclaim “There’s Wynken, Blynken, and Nod!” with the same marveling delight Ebenezer Scrooge exudes when he recognizes, as the spirit of Christmas Past leads him back in time, the fond figure of his first boss: “Why, it’s old Fezziwig! Bless his heart; it’s Fezziwig alive again!”

Scrooge himself will appear in Margaret Martignoni’s grand pageant some four hundred pages after Wynken and friends, waking up after his ghostly night to the giddy realization that he’s been given the chance to celebrate Christmas with newfound joy. The episode from A Christmas Carol is part of the run of carefully chosen sections from classic works—The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Treasure Island, Robinson Crusoe and The Swiss Family Robinson, The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood and My Friend Flicka, Penrod and Little Women—that brings the progress of story to its conclusion in a swirl of tantalizing samples. If I’ve left out all the glories between start and finish—from Edward Lear’s “Nonsense Alphabet” to Longfellow’s “The Village Blacksmith”; from poems by Christina Rossetti, Eleanor Farjeon, and Rachel Field to those by Keats, Shelley, and Wordsworth; from tales of Aesop, Andersen, and the Brothers Grimm to cameos by Peter Pan and Babar—it’s because there are too many to stop and applaud.

“What has become of the old-fashioned family reading hour?” Martignoni writes in her introduction, composed with happy coincidence in the year of my birth. “Once an established custom in the American home, the reading hour has in recent years become more and more of a rarity.” I suspect the custom was honored in some way in our home in my earliest years.3 If my memory of those exact hours is elusive, the tenor of the tellings they likely hosted tempered my becoming with a music that still carries me along. If such hours were disappearing seventy years ago, how much closer to extinction they are today. Even more endangered is the inherent promise of this Illustrated Treasury: that attention which begins its journey with “Lucy Lockett” and “Little Jack Horner” will of course make its way, over the years and between the same covers, to Little Women and Gulliver’s Travels. The infinite riches of this single volume speak of a time when literature was not a discipline but an inheritance; their faithful gathering counts on the incalculable reckonings of a reading life, the life my mother gave me.4

To be continued.

This lovely phrase was coined, in different but reflective context, by George Eliot in Felix Holt: The Radical (1866):

The mother’s love is at first an absorbing delight, blunting all other sensibilities; it is an expansion of the animal existence; it enlarges the imagined range for self to move in: but in after years it can only continue to be joy on the same terms as other long-lived love—that is, by much suppression of self, and power of living in the experience of another.

I should note as well, for old times’ sake, the inexplicably familiar sense of frolic I recognize each time I open The Cat in the Hat with my grandson and follow the rollicking trail of words across the red, white, and blue landscapes of Dr. Seuss’s imagination.

My father, I am sure, was not a participant in whatever family reading group my mom convened. He was puzzled by her devotion to books, and my own infatuation with them. I would place a large bet that he never read a book entire in his life, because it’s a bet I’d know I’d win; other wagers, in valuable currencies, gave me rewards to treasure from his patrimony, but that’s another story.

The title of this section alludes to a phrase—in luminis oras—Lucretius uses in his invocation to Venus, “mother of the Romans,” at the start of his poem De Rerum Natura. Its original context, as translated here by Anthony M. Esolen, offers a nice grace note to these memories:

And since it is you alone who govern the birth

And growth of things, since nothing without you

Can be glad or lovely or rise to the shores of light,

I ask you to befriend me as I try

To pen these verses On the Nature of Things . . .

"their home of more than sixty years had, with mortality’s definitive punctuation, completed at last its slow migration from the present tense into the vacant and redolent release of the retreating past."

The tender and elegiac tone of your loving portrait of your parents, young and then older, is exquisite, James. So well done, and a pleasure to read. I will restack to hopefully attract more deserved attention.

Thanks jim! Boy can I relate although my mom was very much like yours. And my dad similar

Our Sherwood isle remembrances and identical as are the revisits. Thanks for the revisit

Blessed holidays to you Margo and the fam xoxo TT