The Household Gods

A meditation on piles of books and on what we gather and then leave behind.

Note: The following essay was originally drafted several years ago. In some particulars, it reveals its age: it was written before we’d moved out of the house we’d lived in for a quarter-century, in the process dispersing the sprawling library whose entropic reach is herein described. Likewise, references to technology are now behind the times; the digital dangers alluded to, while still relevant, comprise single-minded complaints compared to those that might do justice to the hydra-headed peril posed by artificial intelligence. Nevertheless, in revising this piece as I collect and review my scattered literary output for purposes that seem, with advancing age, both urgent and pointless, I’ve left these orientations unaltered while fiddling with the sentences in order to keep my hand in (in hope of, piece by piece, removing it for good). In any case, I thought to share it here as it expresses themes still meaningful to me and treats some writers now neglected. It’s long enough to be better served in this venue in two parts, and presentation that way will also buy me more time to work through some recalcitrant new writing that is proving slippery to pin down. The second part will be posted in two weeks. As ever, thanks for your attention.

1 :: In a lovely reminiscence in the March 18, 2019 edition of The New Yorker, Kathryn Schulz celebrates a domestic landmark of her formative years: her father’s casually elaborate stack of books, which grew in piles on both sides—and across the top—of her parents’ dresser. Describing the reading life layered into the slow-motion evolution of interest and intent that this “Mt. Kilimanjaro of books” represented (“Or perhaps more aptly the Mt. St. Helens of books,” she glosses that initial description, “since it seemed possible that at any moment some subterranean shift in it might cause a cataclysm”), Schulz muses on the challenge of keeping books organized in any permanent way:

The difficulty is that anything that is perfectly ordered is always threatening to become imperfect and disorderly—especially books in a household of readers. You are forever acquiring new ones and going back to revisit the old, spotting some novel you’ve always intended to read and pulling it from its designated location, discovering never-categorized books in the office or the back seat or under the bed. You can put some of these strays away, of course, but, collectively, they will always spill out beyond your bookshelves, permanently unresolved, like the remainder in a long-division problem.

When it comes to the problem of ordering volumes in our house—to pause for a moment on the vinculum of Schulz’s mathematical metaphor—we long ago lost track of the dividends, divisors, and quotients and have been wandering among errant remainders for quite some time. They’re piled on nightstands and kitchen counters, on the arms of sofas and against the legs of tables, in bedrooms and bathrooms as well as on desks and other surfaces in den and study. They spread through the basement like a benign infestation. When I was asked on my book tour1 how we organized our books at home I said, only half facetiously, “I can’t really say. The piles on the floor have been there so long and grown so tall I haven't seen the shelves behind them in years.”

I’ve been thinking about this a lot lately—well, I’ve been thinking about it for most of my adult life, but the question looms larger now as we contemplate a move from our home of a quarter-century and find ourselves confronted with the most obvious challenge of this change of life: what do we do with all this stuff? It’s more than just books of course, and it’s more than just ours: there are the Xanadu-like storehouses of our daughters’ childhoods; the professionally-informed laboratories of my spouse’s cooking equipment; the accumulated tchotchke’s of school and social lives; dishes and decorations passed across generations; file cabinets filled with paper trails whose destinations have been obscured by time; the boxed remains of the winnowing of possessions that marked the closing and transfer of my in-laws’ homes, sooner or later to be accompanied by similar mute memorials concentrating the disinhabited estate of my own nonagenarian parents. My back hurts just thinking of it all, although both the stuff and the anticipatory pain do me the service of distraction from the harder decisions about where to go next and, when we get there, where will we be from?

2 :: It’s a Saturday morning in July and I’ve enlisted the aid of three helpers—sons of friends—to pack up some of the inessential volumes and haul them to the local library as stock for its next book sale. The boys are here to protect my sacroiliac, but more importantly to keep me honest: the need to keep them busy will spur me to decisiveness as I review spines on shelves and in piles and pull the ones I can live without. How many times have I begun this task previously and ended up with five books—two of those duplicates—deemed fair game for sacrifice after two hours of surveying? My strapping assistants will focus my effort on the task at hand.

Still, the choices I’m making are fairly easy, the flotsam and jetsam of four decades in bookselling providing enough fodder for today’s session—no need to tap more treasured cargo to fill the three dozen cartons we have on hand for the purpose. For me, naturally enough, the best part of the job is the small pile of forgotten enthusiasms I lay my hands on, and put aside to be perused, glass of wine at hand, when the library expedition is complete.

Top of the pile is Bonnettstown: A House in Ireland, a book of photographs by Andrew Bush. It was published in 1989 and, as long as it remained in print, was a staple in the pages of the book catalogue, A Common Reader, which I ran back then. Its ostensible subject is Bonnettstown Hall, an early 18th-century limestone manor house situated in the countryside near Kilkenny. Finding himself captivated by Bonnettstown’s beauty and weathered elegance, Bush visited it—as a guest of the four elderly aristocrats who inhabited it—many times over a three-year period to produce an evocation of the dwelling that is both reverent and candid.

His large, autumnally-toned color images—of rooms and their lived-in, tattered furnishings; cloudy windows softening the sun’s incursions; desks habituated to persistent papers; draperies that seem to be announcing something, like the endpapers of a book of outmoded but resplendent dramatic verse—are saturated by the palpable time that suffuses every nook and cranny of the ripe old manse. An off-kilter lampshade salutes the deep-worn majesty of the entrance hall sofa; tire tracks mark the light snow before the stately front elevation like impatient fingers reproving dust; assorted throw rugs cover a floor like miscellaneous postage stamps juxtaposed by convenience on an envelope; then a doorway frames what might be a fading Vermeer, opening into an absence that is endless yet somehow intimate, like all human relations with time. And that’s the real subject of Bush’s beautifully composed book of visions, not Bonnettstown per se but the household spirits who abide in it, at ease with the past, embedded in it, in a way our more transient domesticity seldom allows.

“Time can never relax this way again,” wrote the poet Richard Murphy in a tribute to his grandmother and the house she animated in the west of Ireland. Murphy’s poem is invoked in Mark Haworth-Booth’s foreword to Bonnettstown, for it captures succinctly the sense of lived experience Bonnettstown itself held fast even in its waning days more than three decades ago, when its time stood still for Andrew Bush’s camera. I wonder what’s happened to it since.

3 :: “No matter how beautifully your life is arranged, no matter how lovingly you tend to it, it will not stay that way forever,” writes Kathryn Schulz in the meditation on her father’s stack of books with which I began. Is there an exception that proves her rule? Maybe life was different for Mario Praz, the erudite Italian critic of English literature who was also a connoisseur of interior decoration. He certainly tried to make it so, as he elaborates in the pages of his memoir, The House of Life, another volume I put to one side as I cull the shelves.

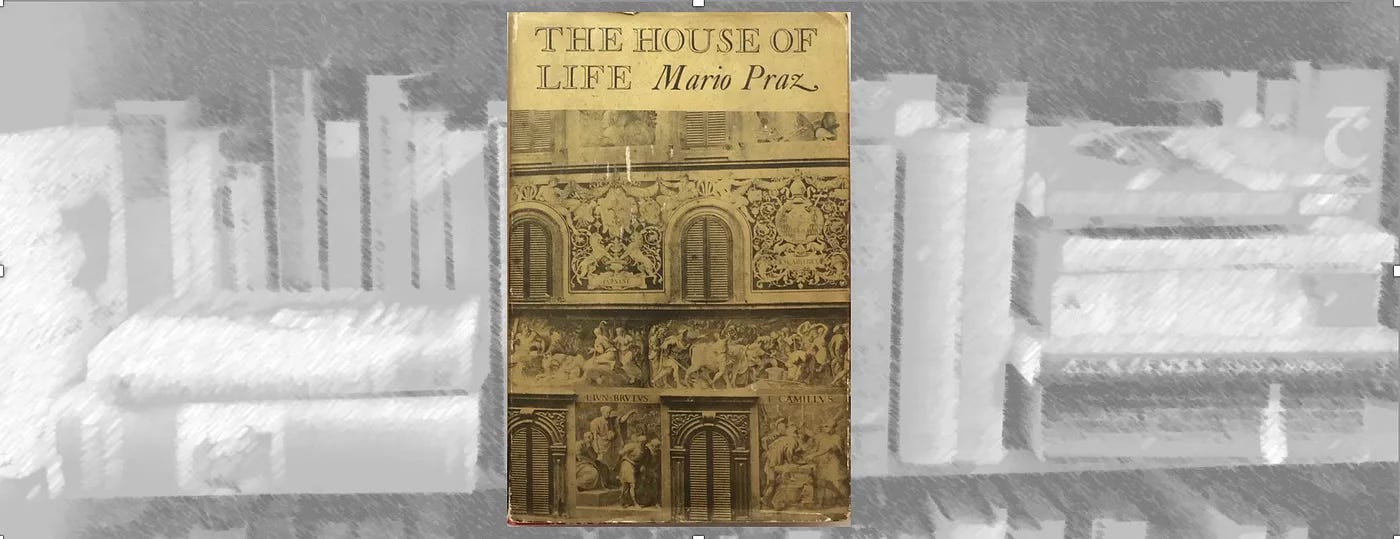

The book is an impressive object in itself, its jacket a regal, elegantly tarnished gold, its binding a colorful burst of red and white decorative paper. The interior pages are a heavy, creamy stock that give the volume a heft weightier than one would expect from its dimensions, which are those of a standard hardcover. I remember when I found this copy, some twenty-odd years ago when it was itself already thirty years old, in The Complete Traveler bookshop, which is now gone, but in those days was on Madison Avenue in New York City, a block or two south of the Morgan Library. From the moment I saw it, on the “Rome” shelf in the store’s Italy section, I knew I had to have it: its golden jacket and sturdy binding fit my hand like a metaphorical glove.

In the weeks that followed, I was so taken with the experience of reading it that I tracked down the rights and republished the book in paperback a year later to share with the audience of A Common Reader. But our edition had none of the allure of that secondhand copy I’d picked up in The Complete Traveler when I knew absolutely nothing about the book, but sensed with a reader’s intuition that it embodied the objective correlative of the sensibility it captured between its covers. Unopened on my desk today, it still seems eloquent.

4 :: Serendipitously I find, paging through old notebooks, that the first time I wrote down thoughts about Praz’s book I also had house cleaning on my mind, and had later edited them for the Reader’s Diary that was an occasional feature in A Common Reader. Here’s what I wrote:

The calendar had barely crept into spring when the air delivered a summer’s day: it was nearly eighty degrees by noon, and I spent the morning trudging up and down stairs to fetch and install our window screens. While I was at it, I even scrubbed the sills of their wintry grime, brushing out the crumbled remnants of last autumn’s leaves (or did they in fact belong to the fall before?). Inspired by my labors—is there any exertion more thoughtlessly ennobling than that recorded in the self-evident progress of cleaning?—I circled through the house, restoring pieces of furniture to their proper poses, collecting the toys and stray shoes that marked our children’s travels through the week, hid piles of mail behind the doors of kitchen cabinets, gathered dirty laundry into baskets (once the clean clothes had been emptied from them), and collected the breeding books from every surface in sight (only to have driven home to me that the miles of bookshelves we’d recently had built had already been outstripped by our reading journeys). Upon my family’s return from their early outing, my daughters seemed determined to undo my diligence, while my wife, noting how pleased I seemed with my weekend contribution to the workaday housework, drolly asked if I had come across the copy of The Myth of Sisyphus she had been reading. I retired to the shower to rinse off the residue of my sense of accomplishment, the only practical result of my efforts being that no one could find anything for the next couple of days. Late that evening I returned, via the polished prose corridors that line the pages of The House of Life, to the cultivated chambers of Mario Praz’s lodgings, where I had dwelled a good portion of the previous week.

Praz, who lived from 1896 to 1982, spent a decade between the wars teaching in British universities before returning to Rome to continue his professorial career. In addition to his command of literary scholarship (which produced The Romantic Agony, the best-known of his many books), Praz was, as I mentioned, a connoisseur of antiques and domestic decor. Under the light of that inspiration, he composed a quirky and magnificent Illustrated History of Furnishing from the Renaissance to the Twentieth Century, and his intelligence seemed to find its true definition inside the suite of the apartment, in a palazzo on the Via Giulia in Rome, in which he lived for many decades, beginning in 1934. Within (and upon) its walls he carefully set the remarkable and storied stars—pieces of furniture (much of it Empire), pictures and sculptures, curios—that together constellated his sensibility.

In form, The House of Life is a simple tour of the author’s home—room by room, exquisite object by exquisite object—with learned digressions into a collector’s recondite passions or a deep reader’s erudition (sometimes the two are charmingly combined, as when “the style of the rosewood sofa-table on which the little bust of Shakespeare reposes” suggests to Praz Keats’s relation to the decorative arts of the Regency, engendering a fascinating small essay on the conversation between Classicism and Romanticism). Each piece has its own history, as well as an association value supplied by its place in Praz’s memory, a value that is enhanced by the sophisticated style of the author’s reminiscence (splendidly rendered into English by the translator, Angus Davidson).

What seems at first a circumspect, dutiful survey of possessions grows to house a many-layered narrative of infatuation and discovery, intuition and fortuity in the pursuit of beauty and personal purpose, a tale as rich and subtle in psychology and expression as the later novels of Henry James. Through Praz’s sketches of his past we inhabit Manchester and the English countryside, Rome at peace and at war, and the intellectual landscapes of an aesthete’s apprehension. We are introduced, through the vehicle of a packet of letters discovered tucked away in what was once his daughter’s bedroom, to intriguing intellectual colleagues such as Italo Svevo, Benedetto Croce, Maurice Baring, and the eccentrically gifted English author Vernon Lee (the excerpts from her letters alone, so tellingly illuminating the “painful slow emergence out of the unreal self of first youth into the reality, prosaic but comfortable and let us hope useful, of mature age,” are, to my mind, worth the price of Praz’s book all by themselves). We spend hours with the author in his quests through the catalogues of antique dealers and auction houses, enjoying vicariously what Henry James himself called “the mysteries of ministrations to rare pieces.” And we recognize at last in this house of life both the temper of genius and the soulfulness of taste, coming to see the apartment on Via Giulia as what Praz himself, in writing this singular and original personal testament, proved it to be: “a mould of the spirit, the case without which the soul would feel like a snail without its shell.”

5 :: When The House of Life was first published in English, Edmund Wilson wrote a long review of it for The New Yorker. The piece, called “The Genie of the Via Giulia,” was later collected in Wilson’s book, The Bit Between My Teeth: A Literary Chronicle of 1950-1965. Characteristically attuned to the tenor of his subject, Wilson infuses his essay on Praz with studious intelligence, as evidenced, with amusing emphasis, by the footnote we can read on page 657 of Bit Between My Teeth. There, with earnest application of attention, Wilson splits hairs about a point in Praz’s comic description, in a book called Unromantic Spain, of a day at the bullfights in Seville in the company of an American couple and their daughter. Noting Praz’s distaste for the cruel spectacle itself (to say nothing of his exasperation with the reactions of his companions), Wilson perfectly details, over a couple of pages, the descriptive enchantment of Praz’s handling of the scene. But what’s most memorable is that footnote, which calls into question a small point in Praz’s description of some animals: “Signor Praz has written giovenchi, bullocks, instead of giovenche, heifers, but, in the light of other evidence, is now inclined to believe that these animals must have been females.”

Were the fabled New Yorker fact checkers embroiled in this debate, I wonder? But not as much as I ponder who the footnote was for, and for whom, more broadly, Wilson—or Praz, for that matter—was writing. Was there once really an audience in a national magazine for the one’s elaborations on the arcane tastes and favors of the other? It’s hard to imagine.2

What’s even more difficult to imagine is anyone reading either of them today. A few years ago, having taken one of Wilson’s old tomes with me as a companion on my commute into Manhattan, I arrived at the office and went straight into a meeting with a group of admirable young colleagues who, it occurred to me as I scanned their faces, had likely never even heard of Edmund Wilson, much less read one of his books. Despite their being in the book business, there was no special reason they should have, but that shock of recognition comes back to me now as I sit in a room in which I can count twenty-seven of his volumes in view, and can remember the exact number of additional Wilson works I counted—and refused to disturb—on an ancillary shelf in the basement this morning as our purge of books progressed: sixteen. That makes forty-three monuments to an author’s industry and a reader’s predilection, collected with care over decades yet bound to be dispersed with anxious abandon when my daughters come into their unasked for literary inheritance and are forced to deal with the hundreds and hundreds of volumes that will surely survive my most assiduous gleaning in the years before I close my last book, and for good. They might do worse than choose one Wilson each to keep as a memento of how a restive youth became their old man.

The tour was for 1,000 Books to Read Before You Die (2018); a few passages from the book are repurposed in this essay.

Here’s the opening of a 1953 letter from Wilson in Wellfleet to Praz in Rome: “Dear Mario: Dr. Melchiori’s book is very able. I think he has got hold of something in his ideas about tightrope walking and the baroque style . . . .”

Our ‘things’, yes, the china so special it was never loved up, the ‘too good to wear’ wool overcoat- but MY library is in fact a true self portrait… it is the radiant family tree of my brain and all that it greedily ate up. It cannot be saved, or even known by anyone else.

I like to sit there in the dawn and feel rich as heck!

Thanks Jim amazing read as I’m trying to sort thru 100 years +of family history best to you and family