Writing (and Reading) Through Time

Notes on Ali Smith, Dickens, and four seasons.

About three-quarters of the way through Ali Smith’s novel Autumn, a young woman named Elisabeth pulls a chair up to the bedside of an elderly former neighbor whom she is visiting in a care home. He’s asleep—or drifting in and out of the past and present of nearly a hundred years of dreams.

She’d brought the chair from the corridor. She’d shut the door to the room. She’d opened the book she bought today. She’d started to read from the beginning, quite quietly, out loud. It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us. The words had acted like a charm. They’d released it all, in seconds. They’d made everything happening stand just far enough away.

It was nothing less than magic.

Who needs a passport?

Who am I? Where am I? What am I?

I’m reading.

The quotation embedded in the passage, the famous opening of A Tale of Two Cities, brings Smith’s readers back, via rhythm and memory, to the first line of Autumn: “It was the worst of times, it was the worst of times.” An appropriate enough invocation of the muse for a purposefully timely novel set and published in the year 2016.

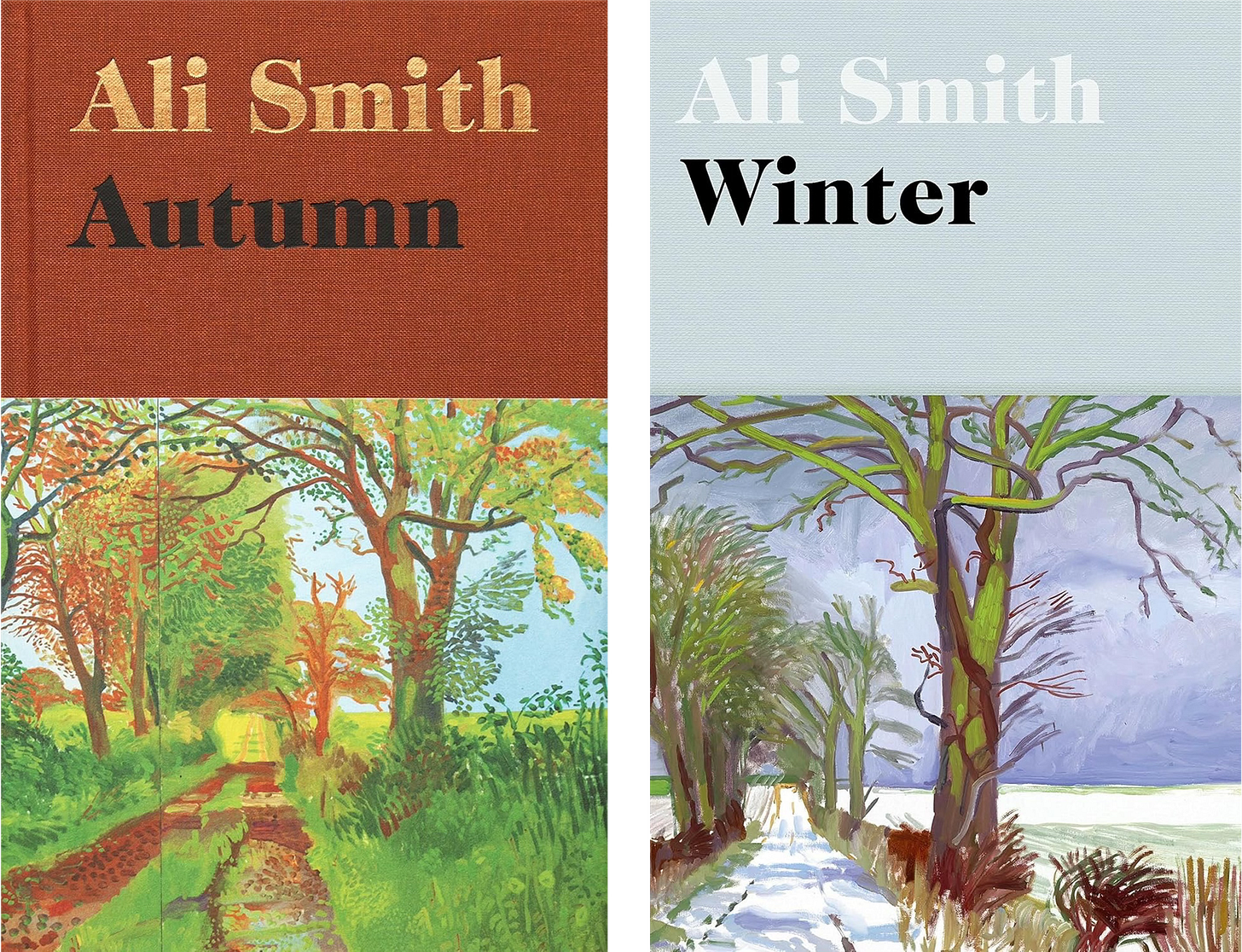

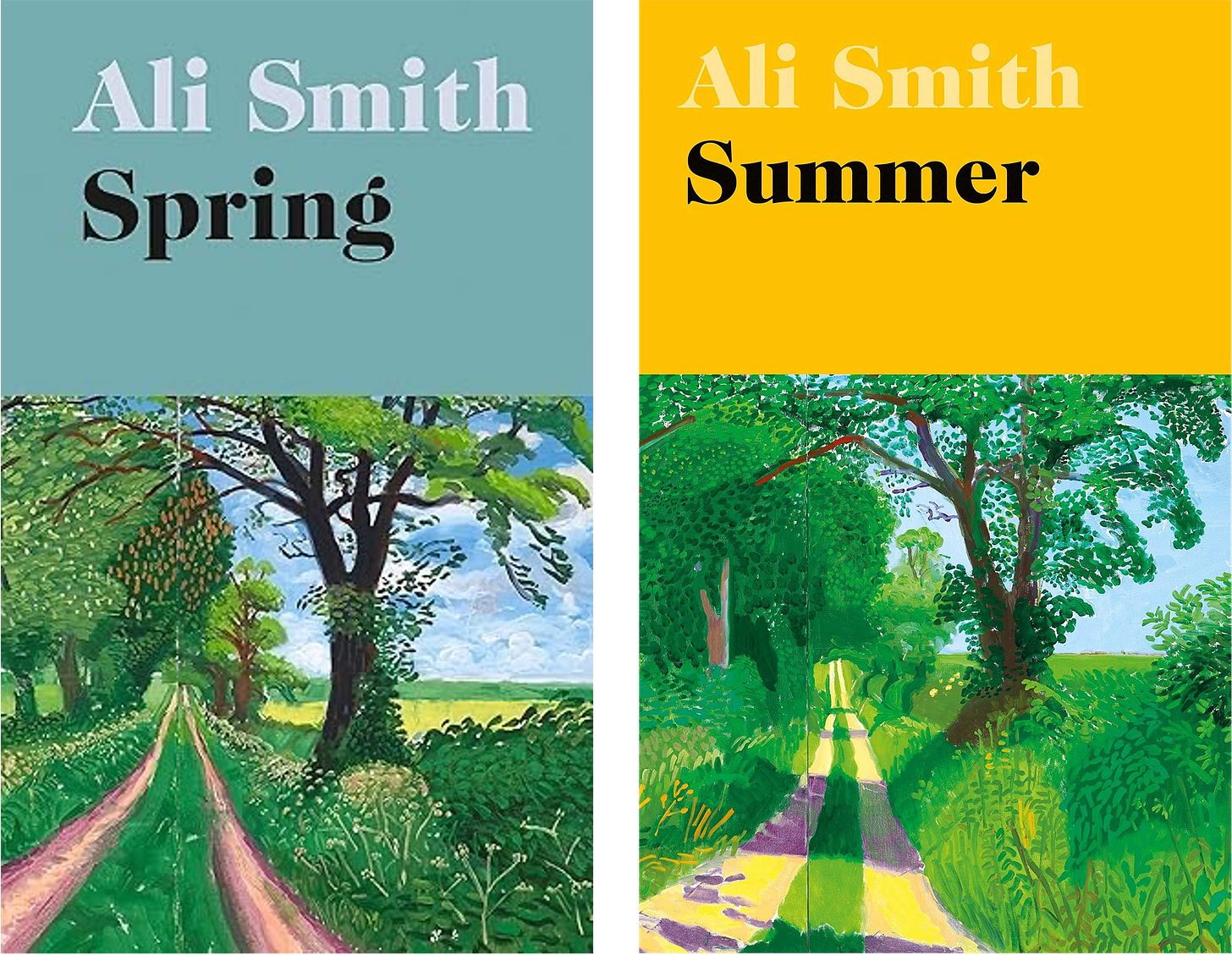

Autumn was the first volume of Smith’s Seasonal Quartet, the final installment of which, Summer, was published in 2020, concluding an ambitious, quixotic, angry, warmhearted, anxious, funny, generous project that was provoked by the tearing of social and political fabrics in both Britain and America in the four years in which the novels were being composed. Steeped in the moods and apprehensions that headlines—migrant crises, immigration, climate change, Brexit, political corruption, COVID-19, Black Lives Matter, Trump ascendent—mark but do not adequately measure, Smith’s quartet is bracing, exhilarating, disorienting; diverting, too, with a cast of misfit characters struggling to find a way to fit in an increasingly unfittable world. While her characters fumble forward through a semblance of real time, in and out of embraces and confrontations, the author composes an experiment that enacts writing through time in a fictive present tense; you might call it a fiction-reel of the news.

What are the novels about? What happens in Autumn, for instance: a woman (the aforementioned Elisabeth) tries to get a passport; she visits an old neighbor—Daniel Gluck—in a nursing home, recollecting as she does so events from their shared past and her girlhood; she discovers, through her elderly friend, the art of the 1960s British Pop Art painter Pauline Boty, whose images, described in prose, are embedded in the text, and then the reader’s mind, like color plates; a fence is erected across formerly common land; Elisabeth’s mother appears on a television program—a version of Antiques Road Show—and falls in love with a TV star from her childhood; all the while the wider world seems to be hurtling toward environmental and political ruin along highways of bureaucratic inanity. Odd, even bewitching in up-close detail, the narration can feel off-hand on first encounter, but ends up cultivating fertile imaginative ground. The subsequent volumes—Winter, Spring, and Summer, which appeared at more or less yearly intervals—follow much the same method, to much the same effect. A longer narrative arc can be traced across the books as well, as imagery and characters weave in and out of the fictional year. If the four books are not tied up into a knot, they are connected along a looping yarn: in Summer, for instance, Elisabeth and her elderly friend reappear when characters from Winter come to visit Daniel to fulfill a mission left them in a legacy.

The books wander off course but find their way back through the kinetic connectivity of Smith’s language, charged with a compulsive range of allusion, etymology, and quotation, and powered with an undercurrent of punning, pulsing energy. Memes of the moment are turned upside down in a deeper well of brooding than their familiar newsfeed settings allow, while a sense of fun animates the narratives with disarmingly resilient cheer. A passage recalling a conversation from Elisabeth’s youth suggests the transformative nature of Smith’s emergent invention:

I want to go to college, Elisabeth said, to get an education and qualifications so I’ll be able to get a good job and make good money.

Yes, but to study what? Daniel said.

I don’t know yet, Elisabeth said.

Humanities? Law? Tourism? Zoology? Politics? History? Art? Maths? Philosophy? Music? Languages? Classics? Engineering? Architecture? Economics? Medicine? Psychology? Daniel said.

All of the above, Elisabeth said.

That’s why you need to go to collage, Daniel said.

You’re using the wrong word, Mr Gluck, Elisabeth said. The word you’re using is for when you cut out pictures of things or coloured shapes and stick them on paper.

I disagree, Daniel said. Collage is an institute of education where all the rules can be thrown into the air, and size and space and time and foreground and background all become relative, and because of these skills everything you think you know gets made into something new and strange.

In their entwining of character and issue, fiction and essay, learning and life, playfulness and purpose, Smith’s seasons recalled to me the skittish and mercurial genius of the French New Wave filmmakers, contemporaries of Pauline Boty, who found a place for whatever crossed their path—old American movies, old master paintings, guerrilla warfare, cups of coffee, tricks of lighting and editing, advertisements, ticks of fashion, flights of philosophy—within their fleet exercises of cinematic unfolding. Reading Smith’s prose is like observing an intelligence as it parses what experience offers as a field for its engagement, creating syntax and grammar on the fly to bestow on inspirations and impressions a beginning, middle, and end (although—as Jean-Luc Godard put it—not necessarily in that order).

Nearly three hundred years ago, in a section of A Treatise of Human Nature called “Of Personal Identity,” David Hume wrote that a person is “nothing but a bundle or collection of different perceptions, which succeed each other with an inconceivable rapidity, and are in a perpetual flux and movement.” A writer attempts to order these perceptions, to give them a shape, just as a story draws and connects the dots between them; what coherence there is comes from the telling.

The intelligence that frames that telling is what we follow through a tale—it pursues a forward motion, even when it’s looking back. The narration of Smith’s Seasonal Quartet—fleet, by turns frisky and mournful, fueled by speech and resourceful in its conjugation of different registers and its shifting strata of story—has a hypnotic energy that pulls us through the imaginative terrain it traverses, a landscape familiar to us because it reflects the flux and movement our newsfeeds bundle for us, remaking reality as a scroll of transient gestures at our attention that we scan without much thought or context. Smith’s telling, and the characters that it carries, leads us into forests of feeling and expression in which thought and context are given their due, not in certainties but in the slow turning of ponder and wonder in which meaning, if not a fixed identity, might be made.

Dickens is the quartet’s muse, invoked not just at the start of Autumn, but in the first lines of the other books as well: in Winter, the first line snarkily intones the opening of A Christmas Carol, replacing the ghost of Marley with a divine corpse, so that “Marley was dead: to begin with,” becomes “God was dead: to begin with.” Spring invokes Hard Times, which begins with Mr. Gradgrind’s “Now, what I want is, Facts,” transmuted by Smith into a bravura chorus of British Brexiteers that begins, “Now what we don’t want is Facts. What we want is bewilderment. What we want is repetition. What we want is repetition. What we want is people in power saying the truth is not the truth.” The onset of Summer is less obvious, but a little digging and there it is, from the last of Dickens’s Christmas-tide tales, The Haunted Man and the Ghost’s Bargain.

That 1848 story begins: “Everybody said so.” Writing a hundred and seventy years later, Smith translates Dickens’s anodyne opening into a combative portrait of her (and persistently, alas, our) historical moment:

Everybody said: so?

As in so what? As in shoulder shrug, or what do you expect me to do about it? or I so don’t really give a fuck, or actually I approve of it, it’s fine by me.

Okay, not everybody said it. I’m speaking colloquially, like in that phrase everybody’s doing it. What I mean is, it was a clear marker, just then, of that particular time; a kind of litmus, this dismissive note. It got fashionable around then to act like you didn’t care. It got fashionable, too, to insist the people who did care, or said they cared, were either hopeless losers or were just showing off.

It’s like a lifetime ago.

But it isn’t—it’s literally only a few months since a time when people who’d lived in this country all their lives or most of their lives started to get arrested and threatened with deportation or deported: so?

And when a government shut down its own parliament because it couldn’t get the result it wanted: so?

When so many people voted people into power who looked them straight in the eye and lied to them: so?

Throughout Summer—as a small family is drawn into an unexpected adventure that doesn’t feel like an adventure, but just one thing after another that sends it into the orbit of a larger family, one that assembles by seeming happenstance from the earlier volumes in the series—the first line of David Copperfield provides another refrain that keeps the ghost of Dickens before us: “Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else, these pages must show.”

Given the question Smith is asking between the lines of these novels—how can we make a story, much less be a hero, in times as frayed and frantic as ours?—it’s apt that she appeals again and again to the patron saint of telling as she conjures her answer. What I’ve written elsewhere about the creative urgency of the Victorian novelist strikes me as applicable to what Ali Smith accomplishes in her quartet: “It’s as if the author has not set out to write a novel, but has been dropped into a pulsing reality he has to write his way through, improvising a narrative out of the available material, much in the way we must construct a life.”

In an oral history of the project posted to her UK publisher’s website (for publishing nerds, the collective explanation of the logistics of the project, from composition to editing to design to production will prove fascinating), Smith talks about the power reading can bring to bear on our understanding of the contemporary world her fiction engages:

It was a case, from Brexit to Covid, of watching how the narratives that get called news, by which we understand and try to assimilate what’s happening to our lives in the world, reached us, and in what form, in what mode of language, and with what purpose. And if we see what happens, however destabilising or unsteadying or steadying or impactful as a form of narrative, then we can start to read it, and reading is everything.

For all its timeliness, Smith’s project is not to document this contemporary experience for later, as it were, but to navigate a path through it that might hearten her readers, to provide something that’s gone missing as austerity economics and a market monoculture has engendered austerity of imagination, a twitterverse of expression. “There was a culture that encouraged us,” the novelist Kate Atkinson tells Smith in another of the latter’s books, Public Library, “and now it doesn’t exist.”

Throughout Smith’s four seasons, encouragement takes the form of a narrative that reflects and seeks to restore the resilience of our nervous systems in the face of relentless misdirection and enervation. I suspect she’d find common ground in this passage from Valeria Luiselli’s 2019 novel, Lost Children Archive:

I’m not sure, though, what “for later” means anymore. Something changed in the world. Not too long ago, it changed, and we know it. We don’t know how to explain it yet, but I think we all can feel it, somewhere deep in our gut or in our brain circuits. We feel time differently. No one has quite been able to capture what is happening or say why. Perhaps it’s just that we sense an absence of future, because the present has become too overwhelming, so the future has become unimaginable. And without future, time feels like only an accumulation. An accumulation of months, days, natural disasters, television series, terrorist attacks, divorces, mass migrations, birthdays, photographs, sunrises. We haven’t understood the exact way we are now experiencing time.

“Plus ça change,” murmurs the ghost of David Hume. “Write through it,” says the ghost of Dickens: there is no understanding of time, no understanding at all, without a telling; which is why Luiselli, like Smith, seeks new ways to keep time in stories.

Writing through Autumn, Winter, Spring, and Summer, Smith weaves threads of imagery and incident, sentiment and spirt, attempting to mend in letters the rent fabric of our increasingly unlettered life, a public turmoil bereft of the encouragement in which readers learn to form the character needed to become protagonists in their own stories, and writers struggle to make fictions that cast a spell that retains some magic once their books are closed.

“An eminent philosopher among my friends, who can dignify even your ugly furniture by lifting it into the serene light of science,” writes George Eliot in Middlemarch,

has shown me this pregnant little fact. Your pier-glass or extensive surface of polished steel made to be rubbed by a housemaid, will be minutely and multitudinously scratched in all directions; but place now against it a lighted candle as a centre of illumination, and lo! the scratches will seem to arrange themselves in a fine series of concentric circles round that little sun. It is demonstrable that the scratches are going everywhere impartially and it is only your candle which produces the flattering illusion of a concentric arrangement, its light falling with an exclusive optical selection. These things are a parable. The scratches are events, and the candle is the egoism of any person now absent—

Isn’t the candle also a book, and the scratches the perceptions of its author, captured in its circle of illumination? And might not that circle light a way forward for a reader through the perpetual flux and movement of her days, and burn long after all egoism expires?